Michigan Supreme Court Considers Whether Cannabis Odor Justifies Vehicle Searches

The Michigan Supreme Court is considering whether the smell of cannabis can still provide grounds for vehicle searches, now that the substance is legal for adult use in the state. During oral arguments on Tuesday, justices grappled with the implications of legal cannabis possession and its interaction with law enforcement protocols. The debate centers on whether the smell alone constitutes sufficient evidence of illegal activity, such as impaired driving or unlawful public consumption.

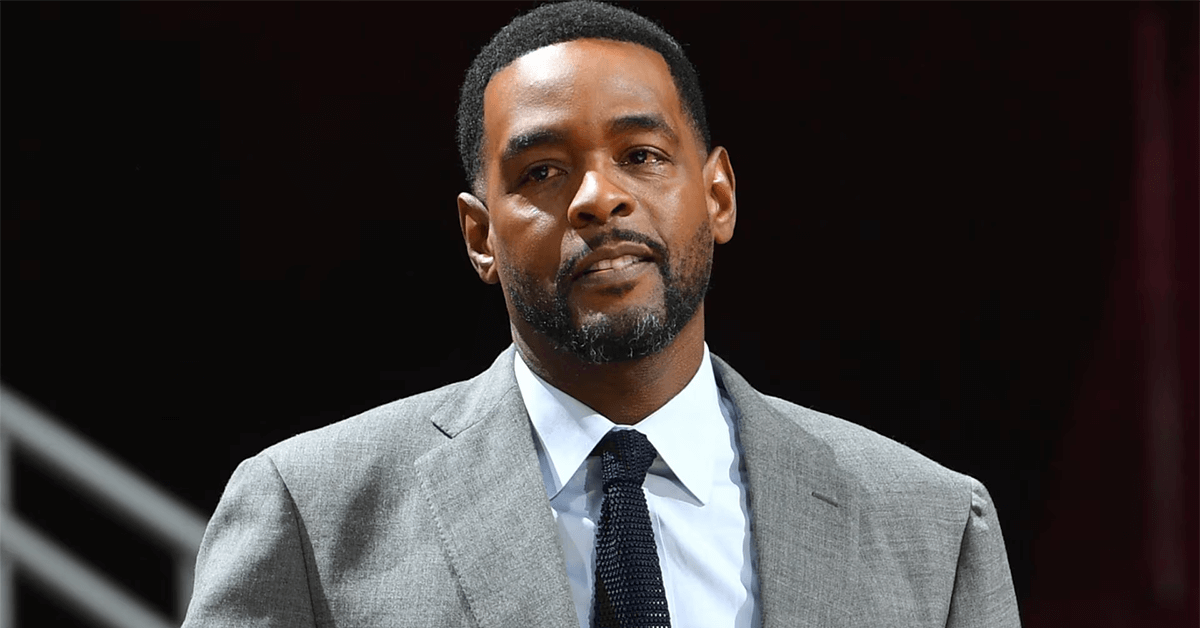

This issue arose from the case of Jeffery Scott Armstrong, who faced weapons charges after police officers searched his car solely based on detecting the smell of cannabis. The lower courts, including an appellate panel, had dismissed the charges, finding that the odor of cannabis, without more, did not establish probable cause for a search.

Case Background: Weapons Charges and Cannabis Odor

The incident occurred when police officers approached Armstrong's vehicle, which was parked in a public area, and claimed to have detected the scent of cannabis. After removing Armstrong and his companion from the car, officers discovered a firearm. Armstrong, who was not licensed to carry the weapon, was charged with multiple weapons offenses. He argued that since recreational cannabis use became legal in Michigan in 2018, its smell should no longer serve as the sole basis for a search or detention.

However, cannabis use in public places and its consumption while operating a vehicle remain illegal, prompting debate over whether officers are justified in investigating cannabis odors emanating from vehicles under these circumstances. Justice Brian K. Zahra raised this point, comparing it to the U.S. Supreme Court's Terry v. Ohio decision, which permits officers to conduct limited searches if they have a "reasonable suspicion" of criminal activity—an evidentiary standard lower than probable cause.

Debate Over Reasonable Suspicion vs. Probable Cause

Justice Zahra argued that a strong cannabis odor could indicate current illegal use, warranting further investigation. He even suggested that it is possible to differentiate between recent and older cannabis smells, stating: "I can tell the difference between an old odor of marijuana and a very fresh odor of marijuana. I don't think it takes an expert to figure that out."

Andrew C. Sullivan of the Neighborhood Defender Service of Detroit, representing Armstrong, countered that the presence of a cannabis odor is not reliable evidence that the drug was being used illegally at that specific moment. Sullivan emphasized that cannabis scents can linger on clothing and upholstery for extended periods, making it challenging to pinpoint the time of use or even whether the vehicle occupants were the ones consuming it.

Judicial Concerns and Legal Nuances

Other justices raised questions about the broader implications of using cannabis odor as a basis for searches. Justice Elizabeth T. Clement asked Sullivan what additional factors might constitute reasonable suspicion if smell alone is insufficient. Sullivan suggested that visible evidence, such as a lit joint or clear signs of driver impairment, would be necessary indicators of ongoing illegal activity.

Justice Megan K. Cavanagh expressed concern over whether legal cannabis use in private settings should be treated differently than other activities, such as possessing alcohol, where legality hinges on context. "How can completely legal conduct give you reasonable suspicion of illegal conduct?" she asked, highlighting the complexities of distinguishing between lawful and unlawful cannabis use based solely on scent.

Law Enforcement's Position: Balancing Legal and Illegal Use

Jon Wojtala, representing the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office, argued that officers should be allowed to investigate a situation if there is a reasonable suspicion of criminal behavior, even if an innocent explanation is possible. Wojtala suggested that a strong cannabis odor directed toward a specific vehicle or individual might justify further investigation. However, Justice Clement questioned the practicality of officers discerning whether a smell originated from recent use or was merely residual.

ACLU's Perspective: Higher Standards Needed for Civil Infractions

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Michigan, participating as a friend-of-the-court in support of Armstrong, argued that reasonable suspicion should not justify searches when the suspected violation is only a civil infraction. The ACLU's Ramis J. Wadood emphasized that under Michigan law, public cannabis use is a civil infraction, while driving under the influence is a criminal offense. He argued that the higher standard of probable cause should apply when officers suspect a civil infraction rather than a crime.

Justice David F. Viviano raised concerns that the ACLU's position would prevent officers from acting on circumstantial evidence, even when it suggests a crime might be occurring. He pointed out that if police need to catch someone in the act of consuming cannabis to justify a search, it could significantly hinder enforcement.

Legal Developments in Other States

The Michigan justices are examining the issue in light of evolving legal interpretations in other states. Just days before the Michigan Supreme Court hearing, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the smell of burnt cannabis alone is not sufficient to justify a warrantless vehicle search. Since the legalization of recreational cannabis in Illinois in 2020, courts there have sought to clarify the limits of police authority in similar contexts.

Next Steps for Michigan's High Court

Armstrong's weapons charges were initially dismissed after the Wayne County Circuit Court judge suppressed the evidence on Fourth Amendment grounds. The Michigan Court of Appeals upheld the decision in 2022, leading the Wayne County Prosecutor's Office to seek review by the state's highest court. The Michigan Supreme Court's decision could have significant implications for how cannabis-related searches are conducted statewide.

The case was heard during a special session at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, part of the court's Community Connections program aimed at increasing public engagement with the judicial process.

Share this article:

Spotted a typo, grammatical error, or a factual inaccuracy? Let us know - we're committed to correcting errors swiftly and accurately!

Helpful Links

Helpful Links